Farmers and Developers

February 2026

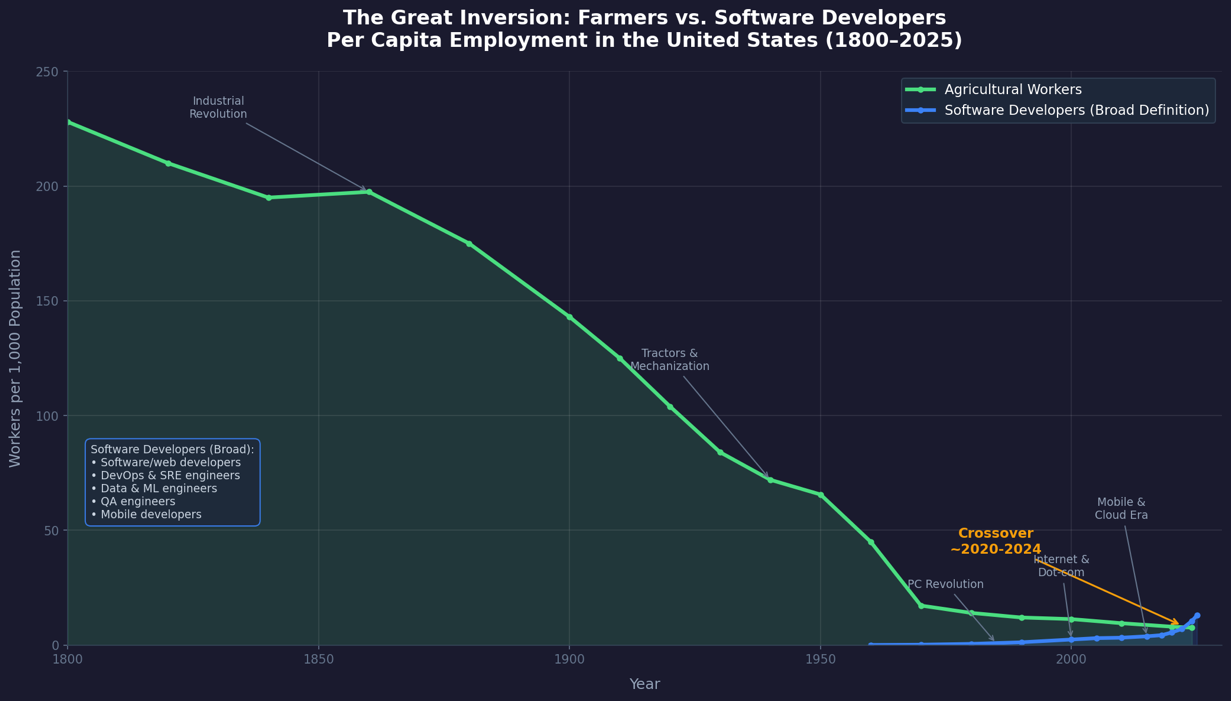

About one out of every 5 people who you’d meet in 1860 would have been a farmer. That was necessary to feed the nation, as the average farmer could produce enough food for himself and 4 other people. Given the large market opportunity, entrepreneurs poured attention and talent into the industry for decades, inventing new processes, mechanical equipment, tractors, and genetically modified crops. As the productivity of each farmer increased, the number of farmers sank. Today, you have to go around to 131 people before you are likely to find one farmer.

A developer trying Claude Code today probably feels a similar range of emotions as did a farmer being introduced to the combine harvester 150 years ago. Initially, awe and amazement at the sheer ingenuity behind the tool. And once that sank in, fear and anxiety at what it may mean for one’s livelihood as they foresaw their job being taken by a machine.

Though unlike the market for food which remains relatively fixed per capita (ignoring the modern tendency to overeat), software has consistently experienced induced demand as its costs have fallen. That is, as costs decrease, tools and products that would have otherwise been cost prohibitive suddenly spring up. In 2007 my team in sophomore EE class developed a step-counter that would not only track your steps, but broadcast the results to the Internet as Wi-Fi signal became available, letting your loved ones follow along with your day, step by step. For the low cost of $699 (plus monthly subscription), the TI-83 sized device could be yours to wear on your waist. Demand at that price point was demonstrated to be slim. Today, there are hundreds of comparable products on the market at much lower price points (granted with inferior designs).

What makes this moment categorically different from the agricultural revolution is the point of reflexivity. The combine harvester, for all its ingenuity, did not design better combine harvesters. John Deere employed engineers who used pencils and slide rules to draft improvements, which were then manufactured by workers operating machines. The tools were dumb. The intelligence stayed in human heads.

Claude Code is different. Engineers use Claude Code to develop Claude Code. The February 2025 release was used to build the capabilities that shipped in May. The May release was used to build what shipped in October. Each version is partially authored by its predecessor.

This creates a feedback loop with no clear precedent in economic history. When a tool can improve itself, the pace of change becomes less predictable. Agricultural productivity improved roughly 1.5% per year for seven decades—a steady, plannable trajectory. Software productivity is lurching forward in bursts, each release making the next release faster to produce.

The implications are disorienting as the half-life of technical skills is compressing. In agriculture, a farmer who learned to operate a tractor in 1950 could still operate one in 1980—the interface remained stable. In 2023 I spent weeks learning how RAG worked. Today, a rag is what you used to clean up a mess.

Yet the same loop that destabilizes individual skills also unlocks new possibilities. Every turn of the crank makes Claude better and makes building new things cheaper. The question isn't whether the loop continues—it will. The question is, what does the world look like where 1 out of every 5 people you meet is a “developer.”